When asked the "what do you do for a living?" question my reply is

usually met with the response that "euthanasias must be so hard". In

reality, most pets are euthanized for good cause and it is much harder

emotionally when an owner can't make the decision to end their pet's

suffering.

Today a stability check was called for a dog that

"wasn't doing well in the lobby" and when I ran to go get it I was met

with a receptionist running towards treatment with the dog. I helped

open the door for her and grabbed the oxygen as she laid it on the

table. As I placed the mask over the dog's mouth the receptionist began

to tell me the patient's history. He had a history of CHF (Congestive

Heart Failure) for the last 3 years, well managed with medication, then

acutely had trouble breathing and wet sounding respirations this

morning.

The dog was given a dose of furosamide and then the

doctor left to talk to the owner. Upon her return I reported that the

dogs color was getting worse and his RR had nearly doubled. But, I was

told the owner wasn't prepared to euthanize and had to think it over.

The doctor attempted to suck out some of the pinkish foam that was

gathering in the dog's pharynx to allow him to breathe better and when

it was clear that it wasn't really helping she left again to tell the

owner that the dog was going downhill pretty fast.

And, as the

owner weighed the decision, I was left standing there with this bug-eyed

dog who was fighting for air. At first he was making up for his fluid

filled lungs by simply breathing faster. This allowed the tiny portion

of his lungs that weren't drowning in fluid to exchange enough oxygen to

keep him alive and pink at first. But by the time the doctor came back

from talking to the owner the dog's color was muddy and he was trying

to sit up in an effort to allow his lungs to expand just a little

further. After the doctor left the second time the dog started to fight

the oxygen mask. He was panicking as he was drowning due to the fluid

in his chest. He tried standing several times, but the increased effort

caused him to breathe even harder and faster with each attempt. I

tried to calm him, tried to hold him up so he could expand his chest

without using extra energy to stand. I tried to deliver the oxygen in

any way I could think of to reduce his stress, and tried to talk to him,

pet him, keep him warm. But the whole time I kept staring at the real

solution -the euthanasia solution in the syringe one foot away. Because

I knew there was no winning this fight. All that could be hoped for

was a peaceful end -soon.

And it eventually happened. He just

went limp in my arms and seized as his heart gave up. In the end the

owner didn't have to make the decision that she dreaded so much. I

cleaned him up and carried him in for her to say goodbye and she got to

skip seeing him panicked and fighting for air for who knows how long. I

don't blame her for her hesitation, though. I know firsthand that

giving the okay to euthanize feels like you, yourself, are killing your

friend, your family member. But as one who spends those last precious

moments with many terminal patients I can say that euthanasia is not

something I fear. In fact it is sometimes something that I sometimes

wish for desperately.

Information for Vet Techs and Vet Assistants as well as cool cases to share and discuss.

Sunday, June 23, 2013

Friday, June 21, 2013

Work Journal: May 23, 2013 Lessons we learned from a dead hamster.

Two techs and a

doctor stand leaning over a table at a dying hamster. The owner had

said goodbye and the euthanasia solution had been injected out of sight

in the treatment area due to the lack of accessible veins in such small

"pocket pets". The heartbeat was down to about 20 Bpm, but we were all

patiently waiting for zero.

The hamster had an obvious abdominal mass that we all wanted to explore and understand, but no poking or prodding was being done because none of us wanted to cause any pain or discomfort to an animal who had already suffered for some time.

Those of us into veterinary medicine do so because of two things: we care about animals, and we are interested in medicine. But, clearly the animal comes first.

So, then the thought crosses my mind that you can still find people today, and the majority of people a few decades ago thought animals were incapable of feeling pain. But here we are, quiet, patient, one of us holding the tiny hamster's hand as we talk about what the mass might be and how sad the adult owner was and what an awesome hammy he must have been to made such an impact.

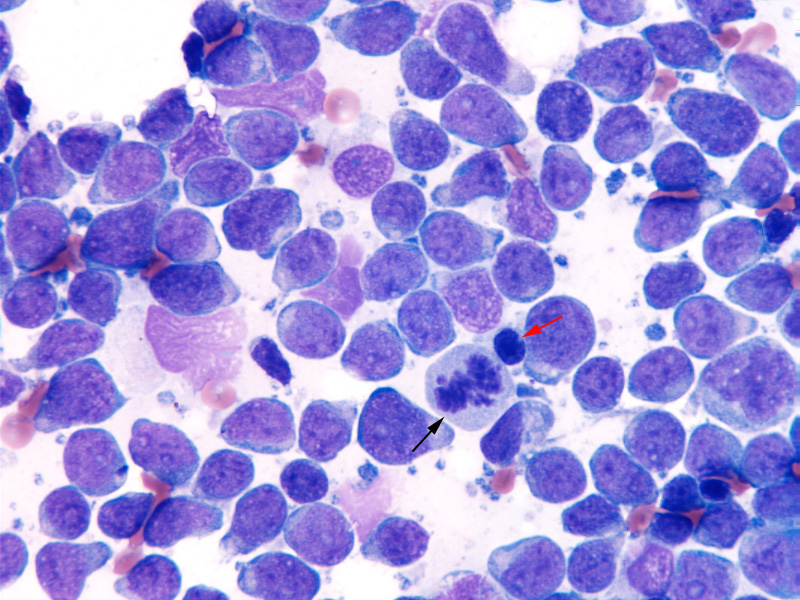

When the doctor felt he was gone she passed the stethoscope to me to double-check. I agreed that no heartbeat was present and handed the stethoscope to the other tech to triple check. Only when we had all agreed that the hamster was gone did we begin to feel the mass and other internal organs to make our guesses. When everyone had finished palpating I took an aspirate of the mass to look at under the microscope and discovered that it was likely a large cell lymphoma which the doctor's reference book said was common for hamsters.

Similar photo of the aspirate under the microscope:

The hamster had an obvious abdominal mass that we all wanted to explore and understand, but no poking or prodding was being done because none of us wanted to cause any pain or discomfort to an animal who had already suffered for some time.

Those of us into veterinary medicine do so because of two things: we care about animals, and we are interested in medicine. But, clearly the animal comes first.

So, then the thought crosses my mind that you can still find people today, and the majority of people a few decades ago thought animals were incapable of feeling pain. But here we are, quiet, patient, one of us holding the tiny hamster's hand as we talk about what the mass might be and how sad the adult owner was and what an awesome hammy he must have been to made such an impact.

When the doctor felt he was gone she passed the stethoscope to me to double-check. I agreed that no heartbeat was present and handed the stethoscope to the other tech to triple check. Only when we had all agreed that the hamster was gone did we begin to feel the mass and other internal organs to make our guesses. When everyone had finished palpating I took an aspirate of the mass to look at under the microscope and discovered that it was likely a large cell lymphoma which the doctor's reference book said was common for hamsters.

Similar photo of the aspirate under the microscope:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)